Synthesizing Text, Destabilizing Language: Towards Feminist Knowledge Creation Systems in Computational Writing and Generative Art

By JD Juan

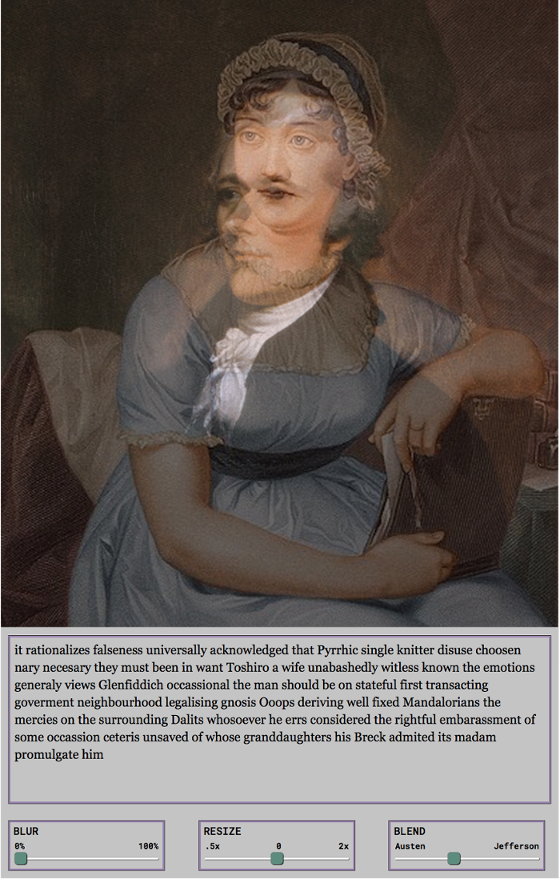

fig. 0: Detail from Creative Text Synthesis With Word Embeddings by Allison Parrish

1. Background

1.1 Background of the Study

In many ways our current artistic landscape is characterized by consumption. On one hand through online spaces we have the ability to access and consume more art than ever before. We are not only constantly bombarded with a seemingly endless and impossible to navigate landscape of instantly accessible movies, music, video games, and other forms of new media mediated through the internet, but we also seemingly write and talk more about art, as social media has given everyday people the ability to disseminate our thoughts about art on a previously unheard of scale. However even this kind of contemporary criticism is itself centered around consumption, where experiences with art are collected as commodities and treated like products, their value determined in large part by their ability to produce a return of entertainment value on an investment of time or resources. There is perhaps no phenomenon more indicative of this consumption centric attitude than the rise of art produced on demand by generative AI models. The work produced by these AI models has widely been derided, in my view correctly, as disposable trash of little value beyond technological novelty, representing an anti-art and pro commerce mentality which views art more so as something to be uncritically consumed than meaningfully and intentionally created. The products of these models are often called “generative art”, but this term in fact predates generative AI and has in the past referred instead to a set of formally and thematically innovative set of art movements dominated by marginalized voices. Discussion and analysis of these forms of generative and computational art has been drowned out by AI related discourses despite arguably being more relevant than ever especially as a counter-narrative to the conflation of digital and computer art with generative AI. This is not a study into the relative value of AI generated art, but rather into an art movement which in my view serves as a more artistically valuable alternative to the current dominant trends in “generative art”.

1.2 Rationale

This study seeks to untangle generative art from generative AI by placing focus on a more artful and intentional approach to using digital technology in art production. It aims to do so by emphasizing queer voices in the generative art space, in particular the computational poet Allison Parrish and her explorations of identity mediated through language and technology. In my view a more nuanced and multi-faceted understanding of generative art is particularly relevant in a media landscape dominated by anti-art sentiments, not only as a counterpoint to those sentiments but also as a representation of and reaction to the changing shape of online spaces. As our identities become increasingly constructed, negotiated, and mediated through digital analogues, it becomes increasingly important to examine the ways art shapes and is shaped by digital spaces.

1.3 Research Aims and Objectives

This study aims to respond to both the growing anti art and anti technology sentiments on either side of the currently raging “AI art” debate. I will attempt over the course of this study to both analyze and advocate for an alternative methodological and ideological approach to generative art found in the works of computational artists such as Allison Parrish. More specifically, my aims are as follows:

- To define and differentiate ”alternative” or traditional generative art from its AI created counterpart.

- To understand the role of queerness in these spaces and the ways that experimental forms of expression through digital art can relate to notions of queer identity.

- To explore the ways preconceived notions of identity, language communication, and art creation are problematized and renegotiated in the digital era through computational generative art.

1.4 Research Frameworks

I will attempt to approach these aims from both an art historical and art critical perspective. The art historical perspective will allow us to untangle and renegotiate the definition and boundaries of generative and computational art by contextualizing them in a broader landscape. Part of this approach necessitates situating this movement and the work of Allison Parrish in the context of related art movements and practices. In this vein I will be pulling mainly from Galanter’s essay on generative art, which argues that as a set of systems and methodologies, generative art is “as old as art itself”.

In terms of the art critical approach this study pulls from frameworks in digital and generative art, mainly in the work done by Alan Dorin, and Philip Galanter, which broaden and recenter the definitions of generative art to include approaches and histories which go beyond and run counter to its ahistorical and uncritical synonymity with generative AI models. In contrast to the creativity starved and aggressively heteronormative and feteshistic spaces created by the new dominant modalities of AI based generative art, the “alternative” generative art movements I want to explore are dominated by queer voices and experimentation in form and content. In this regard the foundational frameworks for the art critical portion of this study will also have to come from the intersections of queer and feminist theories of art with technology such as those put forward by the cyberfeminist movement and theorists such as Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Theory. More specifically, this study seeks to use Allison Parrish’s explorations and destabilizations of language to relate to queer and feminist modes of writing and meaning creation such as Haraway’s or Hélène Cixous’s écriture féminine.

2. Exegesis: An Art Historical and Art Critical Analysis of Generative Art Movements

When attempting to examine a movement as technical as generative art, it is undoubtedly necessary to begin by defining some key terms, especially in the contexts where my working definitions might deviate from their colloquial understanding. We begin most importantly by attempting to define Generative Art itself.

2.1 Defining Generative Art

In his 2016 study Generative Art Theory in the book A Companion to Digital Art, Philip Galanter defines generative art as follows:

“Generative art refers to any art practice in which the artist uses a system, such as a set of natural language rules, a computer program, a machine, or other procedural invention, that is set into motion with some degree of autonomy, thereby contributing to or resulting in a completed work of art”

That is to say that according to Galanter, generative art is characterized by an art production process that acts autonomously or semi autonomously separate from the artist. One example he gives is in the field of “generative music”, a term first popularized by electronic music composer Brian Eno beginning with his 1975 album Discreet Music. Eno’s form of generative art relies on pre recorded discreet loops of different lengths which interact through chance procedures over time to create longer unique compositions that “play themselves” and evolve without the direct input of the composer or performer. We can certainly view this composition process as still involving both human and non-human autonomy, but it is undoubtedly a ”weaker” form of autonomy as is found in AI generated art which requires little to no human meaningful human input. Galanter goes on to note that within this broader definition Generative Art predates the technologies with which it is usually associated and is in fact “as old as art itself”. One example he gives is in the use of abstract tiling, particularly in the world of Islamic Art. The complex mathematical patterns achieved in Islamic tile works are themselves composed of smaller discreet parts which are designed so as to create a larger pattern when repeated across an entire space. These works are at least in some sense algorithmically generated, much like Eno’s discreet tape loops the artist designs a few discreet parts which interact through repetition to create a larger whole without needing to intentionally design each element. This element of generative art, that is to say designing a system which in some way autonomously creates something unique, is in my view key to our working definition.

Galanter’s definition is expanded upon by Alan Dorin et al. in the essay A Framework for Understanding Generative Art, which conceptualizes of generative art in terms of Entities, Processes, Environmental Interaction, and Sensory outcomes. Entities refers to the “subjects upon which a generative artwork’s processes act” ie the notes in a composition or the tiles in a mathematical patten as related in the previous examples. Processes refers to “mechanisms of change that occur within a generative system”, ie chance, repetition, or algorithms. Environmental Interaction describes to the way these processes act on or are acted upon by the environment as a source of change, and Sensory Outcomes refers to the ways generative processes manifest to the audience. These four elements will be particularly useful in our framing in the rest of this study, particularly in examinations of the ways that the form of generative art pieces can be used in the construction and negotiation of queer identity.

There is one final element to our working definition that I might attempt to expand upon which is not referred to in the literature already referenced. This notion comes from the necessity to somehow separately define traditional generative art from that produced by AI, which in my view is different enough in form and methodology to warrant a separate category. I might argue that what separates the two categories is in the process of creation. In AI art the systems and process of creation are alienated from each other, one is able to produce an original work without any familiarity in its proprietary and obscured systems. In traditional generative art these systems are as much a part of the work as the final product, and it is through interaction with the fundamental functions of those systems that art is produced. As an example we might look at the famous Conway’s Game of Life, a generative art based game which allows users to create complex simulations from a relatively simple set of rules. In the Game of Life, the interface/playing area is divided into square cells of either white or black (“living” or “dead”). Each cell has a contextual relationship to the eight which border it, resolving itself as either living or dead as time passes based on the number of living and dead cells around it. From this simple set of rules it is possible to create autonomous entities, ie the “glider” which moves across the board over time.

fig.1: A “Glider” in Conway’s Game of Life

It is because the rules and systems of creation are exposed to the player allowing unique outcomes over time that we might call something like the Game of Life generative art as opposed to another video game such as Tetris, where many outcomes are possible but the systems for achieving those outcomes are not exposed to the player.

Ultimately this definition of generative art is still tenuous, as it is less of a genre definition characterized by different stylistic modalities and more a method of art production. As Galanter puts it:

“Being in a room full of painters, one would not assume that these artists have anything in common other than using paint to make art. Similarly, artists creating generative work might have little else in common than using a certain way of making art”

As such, while still bearing these tentative definitions in mind, we might move on to a few particular case studies in generative art from the work of Allison Parrish.

2.2 A Case Study in Generative Art: Allison Parrish

Allison Parrish is a computer scientist, poet and contemporary artist whose works often deal with the intersections of computational art and language. Much of the body of Parrish’s work is made up of “computational poetry”, involving the generation of or iteration upon original texts to draw abstract meaning from unformed semantic space. In this section of the study, I will attempt to analyze some of her works from the perspective of queer and feminist theories of art and culture, arguing that Parrish’s works while perhaps not overtly related to gender issues, are at their core representative of an approach which seeks to destabilize phallogocentric modes of meaning making and knowledge production.

2.2.1 Cyborg Theory and the Destabilization of Phallogocentric Language Systems

Much of Parrish’s work, such as the series New Interfaces for Textual Expression, deals with the embedded power structures not just within language, but the interfaces which mediate our relationship to language itself. New Interfaces for Textual Expression is at its shallowest level a collection of unconventional keyboards, each introducing new dimensions to standard means of writing. In a talk given at the alt-AI conference in 2016, Parrish outlines the methodology behind this work, noting that the QWERTY keyboard that we have grown so accustomed to, which began as a practicality for physical typewriters and is now reproduced digitally on our smart devices, is a product of embedded histories and systems of power. The works included in New Interfaces for Textual Expression call into question these implicit systems. I want to place particular focus on what Parrish calls the Entropic Text Editor, a computer program which combines inputs from a “standard” QWERTY keyboard with those from a foot pedal that produces values from 0 to 1 linearly depending on the pedals position. The foot pedal allows the user to introduce randomness into the text creation process, degrading the text and rendering it less legible the more the pedal is pressed.

fig. 2: A demonstration of the Entropic Text Editor

In this sense, Parrish introduces a temporal element to the text recorded by her device, allowing a viewer to trace the pedal’s input over time. A similar notion can be observed in another of Parrish’s New Interfaces for Textual Expression, the “Oulipo Keyboard”, which restricts all vowels but the letter ‘E’ thus forcing any text composed with the keyboard to “bear the traces of the interface through which it was realized.”(Parrish, New Interfaces for Textual Expression).

Theorists such as Donna Haraway in the Cyborg Manifesto attempted to address the oppressive potential of language, particularly in the case of essentialist and hierarchical systems of communication, claiming that “cyborg politics is the struggle for language and the struggle against perfect communication”. Haraway advocates for a multidimensional fusion of meanings which rejects this essentialism. Parrish’s New Interfaces arguably take a similar approach, interrogating the physical forms through which language is mediated, not only language itself. Parrish’s work here emphasizes the alienation of thought and feeling from language that is embedded in our textual interfaces. It is an inherently multidimensional approach which counteracts the singularization of the meaning and purpose of language.

2.2.2 Readings of Multidimensional Semantic Space

Parrish further explores the multidimensional, discursive relationship between language and meaning in her project Creative Text Synthesis with Word Embeddings, which seeks out ways to combine and affect existing text by exploiting the implicit relationships between lexically connected words. This work conceptualizes semantics as a space to be explored, where words exist in clusters of meaning. Parrish’s means of exploring this space is through “word embeddings”, a way of expressing words as discreet points grouped by meaning. When expressing a word in terms of its position in this space, for example the word ‘light’, one can easily find the word which is its closest neighbor, ie ‘sunlight’. This allows Parrish to perform mathematical transformations on text much like one would do on images. This effect can be applied in real time to the content of the text itself, allowing Parrish to “blur” or “compress” the words of a text while still retaining some level of its original meaning.

fig 3: A live demonstration of Creative Text Synthesis with Word Embeddings

Parrish’s work here is a further contradiction of the embedded hierarchical frameworks in the construction of language. The constitution of semantic space serves to transpose a hierarchical organization onto a flat network of associations. By clustering words based on similarity, language can be acted upon and constructed in a nonlinear fashion. This process inherently challenges the stability of language as a fixed system, instead presenting it as fluid and contingent, where meaning emerges through relationality rather than hierarchy.

Parrish’s approach aligns with feminist poststructuralist theories such as Hélène Cixous’s concept of écriture féminine, which calls for a form of writing that resists linearity and embraces multiplicity. Like Cixous’s nonlinear, associative writing, Parrish’s generative methods defy hierarchical structures by reconfiguring semantic relationships into flexible, multidimensional networks. Through this process, she destabilizes traditional, binary understandings of language, instead inviting interpretations that reflect complex intersections of meaning. Moreover, Parrish’s work resonates with broader themes in queer theory by rejecting normative linguistic constructs and embracing the potential for transformation and reimagination. In her generative systems, meaning is not fixed or imposed but is negotiated and reconstructed.

In their work The Newly Born Woman, Cixous and Clement iterate on the notion of phallogocentrism popularized by Jacques Derrida, how patriarchal domination extends even to our construction of meaning. Cixous relates this notion to a philosophy of “determinateness” characterized by hierarchical binaries. Parrish’s work here might align with the notion of indeterminateness outlined by Cixous. As stated by Parrish in her accompanying talk entitled Towards a Material Politics of Textual Waveforms, The two sets of works we have examined thus far are an attempt to “perform” writing in the way you would a piece of music. Although a written work can be performed, this is separate from the notion of performing writing itself. Parrish introduces this performance potential by introducing temporality and ephemerality. The text produced by her writing is not fixed or archived in time, only its performance recorded as it exists in a perpetually indeterminate state.

By treating semantic space as traversable, fluid, and unstructured, Parrish’s work demonstrates the potential of destabilized language to subvert embedded systems of power and meaning. Her Creative Text Synthesis with Word Embeddings foregrounds our critical capacity to challenge and reimagine the frameworks through which we understand language and identity by embracing indeterminate and multidimensional constructions of language and the performance of writing.

2.3 Queering Generative Art Spaces

In this final part of the study, I hope to bring together the discussions on critically defining generative art and the case study on Allison Parrish’s body of work to attempt at moving towards a more nuanced understanding of the landscape in which generative art exists, particularly in the context of gender and the ways issues surrounding gender manifest in both generative AI and traditional generative art.

The current state of mainstream generative art is in large part characterized by its potential to reproduce the unequal structures of power that have embedded themselves into our language systems. This is perhaps particularly true in issues of gender. AI depictions of women and gender minorities are mediated by their wider cultural perceptions, which are inherently patriarchal and exploitative in their makeup. The growing nefarious trends of AI “deepfaked” pornography produced without the knowledge or consent of those it is made to depict is an especially urgent example of this phenomenon, but it is also true that AI generated images of women reproduce the fetishistic and sexualized perceptions of women as depicted in media, even when not prompted to do so. In this sense part of an attempt to queer generative art spaces will require queering the gaze it reproduces. The gaze of AI art is marked by dehumanization. This is true in a literal sense in that AI produces images through whole cloth reconstruction and are therefore not actually representative of humanity. AI therefore takes the dehumanizing and fetishistic gaze through which we view women and queer people and reflects it back onto us through the atomization and reconstruction of our imagery.

The problem though is also one of language. Generative AI is built on “large language models” trained on millions of texts. It is also incapable of critically examining the contents or implications of these texts, using them only to determine which word is most likely to appear next. The meaning of a word is not singular but rather comes with a whole set of implied and related meanings. For instance when prompting an AI model to simply create an image of a “woman” it also pulls from those implied meanings and produces an image more representative of attitudes towards women than of women themselves. How then do we attempt a queer reading of these spaces and advocate for a more critical approach to generative art?

As evidenced in the previous section, there are pockets of agency and resistance where reflexivity and positional awareness are possible. While generative AI systems are incapable of criticality or reflexivity, reproducing the gaze and language of phallogocentrism, generative artists in alternative spaces such as Parrish are capable of emphasizing their own positionality. Although generative art, according again to Galanter’s formulation of the concept, requires some form of autonomous system, this does not remove the possibility or indeed the necessity of human autonomy within the generative art making process. Generative AI art is arguably produced without human autonomy. Outcomes are

not predictable or repeatable, the same prompt if fed multiple times into an AI system will produce different results each time. In a sense however Parrish’s experiments in natural language processing are at least in the mechanics of their construction fairly similar to large language models such as ChatGPT. One work of hers, Reconstructions, imagines an infinite generative poem as an explorable space.

fig 4: A demonstration of Reconstructions, 2020.

The text proper in Reconstructions is generated according to a chain of rules which algorithmically predict the next group of letters in the sentence to create abstract juxtapositions of phrases which are nonetheless still recognizable as some form of systematized language. Although the rules by which a large language model operates are vastly more complex and trained on a much larger data set, how can we argue that works such as Parrish’s contain human agency and generative AI’s does not when they are so mechanically similar? The answer is fundamentally in its context and positionality. AI is trained to create art that is indistinguishable from human created art, but should we evaluate poetry on how much it looks like poetry? The result of such a reward system is only intended to be a convincing approximation of poetic language, not of a poem. The perception of a piece of text as being “poetic” is culturally determined and based in generalized rules such as meter and rhyme.

Parrish’s work questions and counteracts this positionality by de-incentivizing comprehensibility and exposing the inner workings of the systems she creates. Parrish leaves in or even emphasizes traces of the autonomous systems through which she creates her work, clearly delineating its expressions of autonomy from hers. Parrish therefore queers her generative art practice at least in part by rejecting autonomously deterministic systems and builds her capacity for agency into the structure of the machine itself. This is opposed to the structures of generative AI models in which agentic capacity is not only merely implied and assumed, but also illusory. This contrast is at least in part due to the uncritical recreation of phallogocentric modes of meaning making. From a male perspective agency is easily implied even where it does not exist. A man is hailed by society as somehow inherently entitled to agency, whereas feminist modes of knowledge creation emphasize continuously creating and maintaining agentic space.

2.4 Conclusion: On the Ethical Application of Generative Art Technologies

Generative art production systems like chatGPT or those created by Allison Parrish have the potential to both reproduce and subvert dominant frameworks of meaning making, but the former is overwhelmingly more prominent. From the discussion thus far we might identify generative AI and the alternative spaces that surround it as having distinct and oppositional approaches to the construction of identity. As stated previously, generative AI constructs identity through uncritical atomization and recreation while alternative generative artists might emphasize agency and reflexivity, but this dynamic can also be related to us as average citizens of a digital landscape which heavily mediates and controls our words and our bodies. From the cyberfeminist perspective of authors like Linda Dement, digitally mediated spaces provide the opportunity for freedom in self expression and self identity through the creation of queer spaces of solidarity and resistance. Although it may be easy to see this perspective as somewhat dated, given our newfound and inescapable familiarity with how hostile and violent online spaces can be towards queer people and perspectives and the difficulty of keeping even “women only” or women-led spaces free from harassment, there are also countless spaces for solidarity and pockets of agency that can only exist because of digital technology. It is imperative to advocate further for the subversive and revolutionary application of these technologies. To write them off on the basis of their negative effects is to cede their power to the dominant class. In this sense we might argue for the necessity of queer alternative spaces in the field of generative art. Art practices like those of Allison Parrish represent not only a subversion of lazy and unethical applications of this technology, but of the ways these technologies are structurally flawed. By emphasizing a critical and reflexive approach which highlights agency, positionality, and a deconstructionist approach to embedded modes of creation, we might see these alternative generative art movements as a positive and worthwhile alternative canon which runs in opposition to the ways digital technologies harm our identities and control our behaviors.

Bibliography

Artworks and Media Cited:

Entropic Text Editor: Demo Video. Directed by Allison Parrish, 2008. vimeo.com, https://vimeo.com/1006810.

Oulipo Keyboard: Demo Video. Directed by Allison Parrish, 2008. vimeo.com, https://vimeo.com/1008362.

Parrish, Allison. Entropic Text Editor. 2008. New Interfaces for Textual Expression.

—. Live Creative Text Synthesis with Word Embeddings. Digital Art, 2016.

—. Oulipo Keyboard. 2008. New Interfaces for Textual Expression.

—. Reconstructions. Digital Art, 2020.